Better Drowned Than Duffers If Not Duffers Won't Drown

We need to equip & trust our kids to take risks - and send them off to sea

My 8-year-old helmed a boat outside the harbour in Dublin Bay for the first time recently. She was calm, competent and able to deal with the chop and gusts we faced in a decent offshore breeze. She was not, in any way, a duffer. Thank the Lord.

We’re reading Swallows and Amazons together at the moment, and there’s this iconic message in it, a telegram that comes back from the father of the kids in the story from his warship in the East China Sea:

Better Drowned Than Duffers If Not Duffers Won’t Drown

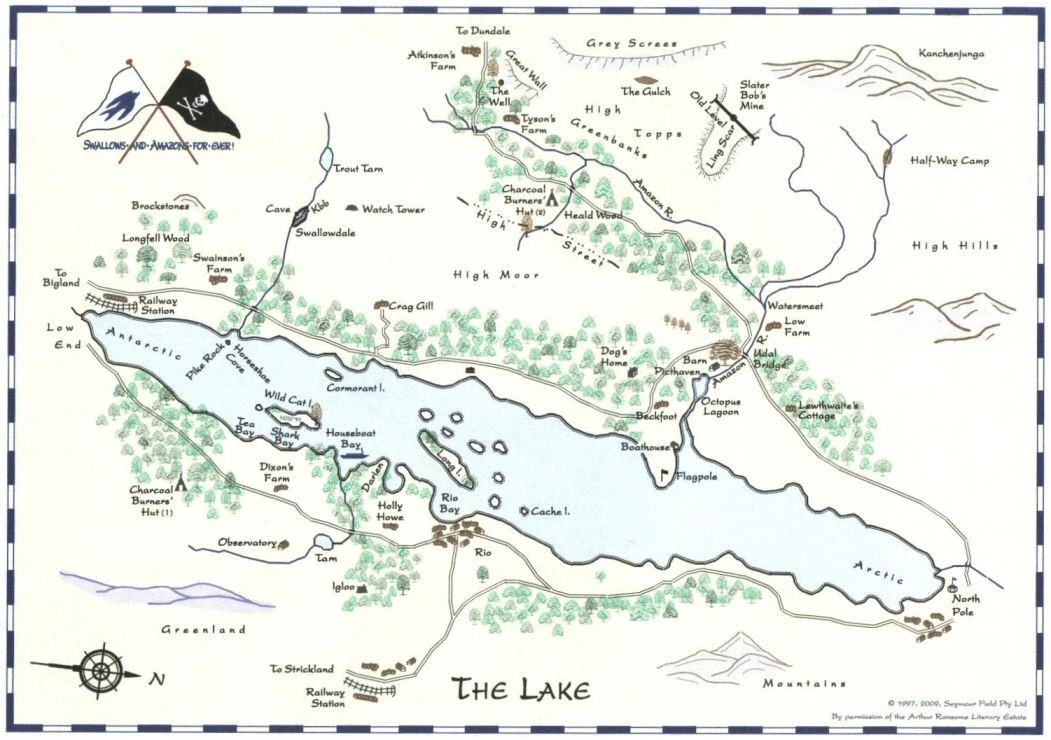

In the book, a group of children (the Walker family siblings) are on summer holiday in England’s Lake District and eager to sail their small boat Swallow to an island and camp there, unsupervised. Their mother, uncertain about allowing such a dangerous expedition, telegraphs their father (a naval officer away on service) for his approval.

The children and their mother take the terse response as a greenlight for their adventure. The father is saying “Yes, they can go”, but adding that if the children were “duffers” (olde slang for incompetents), they’d be better off drowned. The implication is that he trusts they won’t, but being a 1920s dad he’s not going to heap praise on them, he states it all very indirectly. The telegram’s second clause – “if not duffers won’t drown” implies competence, or even goads the children into having confidence in their own ability. As a respected naval officer there’s a clear underlying message: Don’t show me up by being idiots on the water, because if you do, you’re essentially dead to me.

The kids - ranging in age from a seasoned 12 years old down to just seven years of age – embark on a series of unsupervised lake adventures that would make the modern helicopter parent vomit with horror They sail the length of the lake at night, entirely unlit, with no navigational aids. They tend open fires constantly. They all possess knives. They wander into the hills to meet strangers and handle snakes. There is not a single mention of a buoyancy aid or lifejacket in the whole book, despite the youngest child being a demonstrably weak swimmer who can’t handle being out of his depth. Their mother, consumed with her toddler, checks in on them with random visits every 72 hours or so.

So to recap, four children (and their two friends) are free-range sailing around a lake and camping self-sufficiently on an island, with adult check-ins approximately every third day.

It is, of course, a work of fiction and a different time, both in terms of risk and parenting styles. But what you see is a bunch of kids taking risks, making stupid and potentially dangerous mistakes, and learning rapidly from them. They adopt a hierarchy based on seniority, mirroring their father’s military values. John, the eldest and most competent by far, is Captain and thus calls the shots and is responsible for boat safety. Susan is next in line and thus first mate and takes on a maternal, responsible role, feeding the crew and generally thinking about the run of the day. Then come the two youngest: Titty is the able-seaman and Roger is ‘the boy’. Titty (9) is inexplicably left alone on the island for an entire day at one point, and ends up rowing off into the darkness before spending the night at anchor, alone, in a wooden dinghy. Their adventures on the lake largely, thankfully, go without serious consequence. (Until the sixth book in the series, where they accidentally sail to the Netherlands).

For my eight-year-old daughter, the prospect of this wild, foreign autonomy is almost too exciting to bear. Reading the book keeps her awake rather than sending her off to sleep.

Back in the real world, we’re at a point with her where she is craving greater challenges. She has been sailing a boat with others and now wants to turf out the passengers and sail a boat solo. She wants freedom AND responsibility, to quote Austin Powers, and I want to give her as much as she can handle, without putting her in a position where she’ll scare herself out of sailing. So we’re judging her ability and loosening the tethers gradually so she gets to risk failure, and learn more quickly by doing so.

And eventually, hopefully without too much delay, we’ll trust fully that she’s not a duffer, and won’t drown, and we’ll let her disappear off from the end of the slip in a boat without watching hawkishly from a nearby safety boat.

Trusting that someone in your life isn’t a duffer is a big moment. Trust is the bedrock of partnership, whether that’s in a family, friendship or business. It’s the stuff of big milestones: giving them the car keys for the first time means you trust they’re not a duffer. When you walk your daughter down the aisle, you’re trusting that she and her chosen partner are not duffers. After my father died, I found an email from him to my uncle saying that he ‘never had to worry about Markham’, which is something he never said directly, but which I felt implicity, only after winning a race in a world championships aged 21. Trust came slowly.

DUFFERS IN THE WORKPLACE

In business, some companies bake trust into policy. They make sure they don’t hire duffers, then they don’t treat them like duffers. (Plenty of companies hire people who aren’t duffers, then impose policies that treat them like huge duffers - this does not breed mutual trust). The most famous example of this is probably Netflix, and their vacation and expenses policy, which comes from their now-infamous Culture Memo.

Our vacation policy, for example, is two words: “Take vacation.” And our expenses policy is just five words: “Act in Netflix’s best interests.” This (almost) no rules rule gives employees the freedom to exercise their judgment.

That means no cap on expenses, leaving the user free to determine what’s in the company’s best interest. Typically, the more senior you are, the bigger your expenses limite. In the book ‘No Rules Rules’, they describe a scenario where a new 4K TV was accidentally thrown out. A junior staffer spotted it, realised that they absolutely needed it for the morning when a media review was taking place, and went out and blew thousands of dollars buying one so that it would be there in the morning. Typically a junior staffer would have to jump through approval hoops, but because he could simple ‘Act in Netflix’s best interests’, he did the right thing and all was well. He was not a duffer.

It doesn’t always work out. I spoke to a CFO of a unicorn recently who had to undo a free-range policy like this because the culture and structures weren’t in place to support it yet. And that’s one of the big things with trusting people not to be duffers. It’s often on you to ensure they’re not. Because if you trust them, and they do the stupid, damaging things that a duffer naturally will if unsupported and untrained, you’re the bigger duffer for having trusted them.

As parents, we all want to be able to give our children maximal practical freedom. But as with that unicorn, that’s only possible when we put the support and structure in place to make sure they’re not duffers and never will be.

In Swallows and Amazons, the father had clearly instilled sufficient seamanship in his older kids, and and understanding of cooperation and militaristic structure in the entire group, to have faith they, collectively, wouldn’t be duffers and thus wouldn’t drown. When he said ‘If not duffers won’t drown’ he already knew they weren’t, and wouldn’t, because he’d ensured they weren’t duffers himself.

How you set up your non-duffers, at home or at work, is entirely up to you.