Know your systems

Know where the bungs & mallets are.

One evening in the summer of 2003 I was on a boat full of teenagers, thrashing upwind through lumpy seas en route to Antigua in the Caribbean. We were part of a small flotilla of 50-foot sailboats I was in charge of at the time, all of the boats manned largely by teens, with two or three ‘grown-ups’ (most of whom, like myself, were below 25 years of age) in charge.

As evening became night a call came through on the radio. One of the other boats was filling with smoke and taking on water through an aft cabin. Either of those things is alarming. Both at once is terrifying. The skipper thankfully was a cool head and, miles apart, we calmly worked through the few things we figured it could possibly be over the VHF radio until we landed on the problem. A $2 jubilee clip had come loose on an engine exhaust hose. With the clip in place, the hose and its exhaust smoke usually exited through the hull at a point that would, if the boat was flat & level, sit just above the waterline. But heeled over as they sailed upwind, that opening was now underwater most of the time, and because the hose had popped off, the smoke that should have burbled out into the seawater was now filling a cavity behind a cabin where three kids were meant to be sleeping, while at the same time seawater was rushing in and sloshing about aggressively.

The situation was distressing but the solution, once diagnosed, was pretty simple: tack over so that the boat leant the other way, raising the hole through which the exhaust hose exited the boat above the waterline; turn off the engine; and then find and reattach the jubilee clip.

Of course, it was only simple because we all knew the systems on those boats inside and out. One of the greatest things about working at Sail Caribbean was the preparation. The staff were a gang of unusually competent and resilient twentysomethings, and the first week of the summer was devoted to learning the boats from stem to stern, then running on-the-water simulated emergency drills about all the things that could go wrong. Loss of steerage, engine fires, cabin fires, loss of electrics, blocked pipes, leaks, medical emergency, mass hysteria. You name it, we gamed it out. We learned not only the various systems on the boats, but created our own procedures and processes to handle most situations and permutations.

Boat systems (like, say, the one below) can be intensely complex. Ours were floating caravans, so the systems were all pretty domestic. But you still needed to know every line, every pipe, every valve & cable, in case you got a call in the middle of the night from a captain who suddenly found herself with a two-pronged disaster unfolding in real time. Or, in case the emergency was on your own boat.

Knowing the systems that keep you afloat is generally a good thing to do. Some people choose to ‘stay high level’ and refuse to get into the weeds. To them, I say this: I don’t want you on my boat. If you don’t at least show curiosity about the underlying systems, I don’t believe I can rely on you in an emergency, or when other surprises show up. You want to work through problems with people equipped to help you tackle things in a logical way. You want people who carry parts of the equations in their heads at all times. You want them to know where the bungs & mallets are, and how and when to use them.

When I landed at WWE in 2019, a huge technical project was coming to its climax, a massive content and systems migration that would have a huge impact on my next few months at the company, and dramatically change the experience of WWE’s most valuable digital users, much of which I would be in charge of.

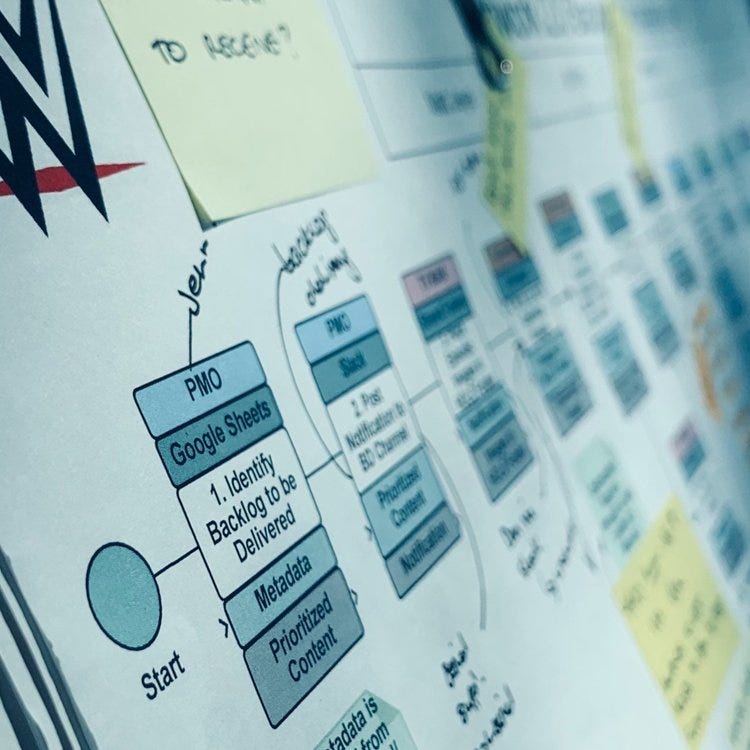

I threw myself into understanding the content systems and the underlying engineering on both sides of this migration – new and old, front-end and back-end. Like a man possessed, I wallpapered my new office with process diagrams, Carrie-from-Homeland-style, highlighting and annotating them with scribbles, arrows and post-its. For my first two weeks, my new team met me in strobe flashes of intensity as I pulled them in to help me tease sense from a chaotic mess of flowcharts and process diagrams, soaking up their explanations with a maniacal fervor. What’s this thing here? Who owns this? Why was it set up this way? They would tell me later, when we all really got to know one another, how insane they thought I was.

It was oddly satisfying, though, and I was extremely glad I’d done it when, two weeks in, the project hit an impasse with a disagreement about how ready we were to make this migration. On one hand, some claimed we were on the cusp of completing this huge task, a culmination of months of effort with teams in three countries all working together, and we should carry on through. Facing them was one particularly livid engineer who said he had identified a risk that could mean some content – an untold quantity, in fact – could effectively be lost in limbo as we repathed every file and asset post-migration.

Somehow, the casting vote in that packed, tense conference room fell to me, the newcomer. I asked a few questions based on the systems and processes I had gotten to know from my manic wallpapering, and the answers led me to side with the irate engineer and push the milestone out until we could be certain it wouldn’t result in a messy, costly roll-back. I might not have had the confidence to make that very uncomfortable call had I not gone deep, and fast.

Many people master breadth of knowledge, the mapping of thin, superficial layers & networks, and can get by just fine by so doing. They understand the ‘who’ and the ‘what’, and some of the ‘where’. But the people who manage to match breadth with depth, the people who add an understanding of the ‘why’ and ‘how’ at least in some key, critical areas, are the ones who make the difference. They are the ones equipped to be decisive in a pinch. They don’t have to spend time gathering intel when there is no time to gather intel. They’re ready to act, and act confidently. Decisions that seem hugely intimidating to others come easily to them. Want some business jargon? These are your 10Xers. These are your bias-to-action, key-outcome drivers.

On a racing boat, on a big boat specifically, you’ll find them at the back, and at the very front, where it’s critical that knowing how key, interlocking systems on and outside the boat need to work together is second nature.

At the bow, you need someone who can think five moves and half a mile ahead of where you are. The bowman is always calculating, like a poker player, the odds of what maneuvers they’re going to be asked to be ready for. As the slanted, slippery deck bucks like a bronco under their feet, they’re mentally mapping out how to preposition ropes, clips, sails and spars for the most likely next maneuver. What maneuver that will be is ultimately decided at the back of the boat where the helm, tactician and mainsheet trimmer (the latter two often the same person) are mapping out short-range strategy based on patterns of wind and tide, the positioning of the competition and how all that comes together dynamically. They have the headspace to think about that while at the same time driving the boat as fast as possible because they innately know the systems well enough to understand how the boat is running just by feel, by how it moves under them, by keeping a few key visual cues in their peripheral vision.

And, of course, in all of these situations – on the caravan boat full of teens, in the WWE conference room, on a high-performance sailboat – the key system you have to understand as a leader is the human one. You need to know that human system and all its constituent parts are likely to work in a given moment, in a given situation, so you can decide whether or not to lead them into it. Will they perform? Will they freak out? Will they know where the bungs & mallets are? During staff training at Sail Caribbean, were weren’t just teaching people the systems, we were evaluating the system that was the staff, so that we could group them into functional sub-systems. At WWE, I had already done a parallel dive on the various teams adjacent to mine so I knew who to listen for, and to, in the conference room. And in any sailboat race, you’re not just keenly aware of the capacities of your own team, you have to bear in mind the capacities of the systems that surround you, and their breaking points.

Of course, if you’re a leader, the hope is that you have been deeply familiar with many systems, human and otherwise, and you get this, and the systems you’re relying on to keep you afloat are ones you’ve built yourself, based on that experience. You know where the bungs & mallets are, and you know that all the other people in your system do too - that’s why you have them there.