I’m building & raising funds for a business at the moment – a brand new entity that has, as a constituent part, a two-sided network. Building a network-reliant business is hard (Go read this book!). Building any network is hard, frankly, even if you consider yourself rather good at it. The hardest part of building a network is establishing it, getting the first individuals on board – getting the momentum going, or in a human sense, being the new kid in school or making friends when you move to a new city.

A network’s value is intrinsic, the value in either side lies in the other, and the opportunity it presents to them. How does anyone know at the beginning that it’s going to be valuable? Well, you look at the connections, what they say about each other and what they offer. What and whom do those connections connect you to? How brittle or strong are those connections, really? How long will they endure? What do they say about the node of the network you initially attach to? Is the effort you’ll expend building the network likely to be returned to you? Is the juice worth the squeeze?

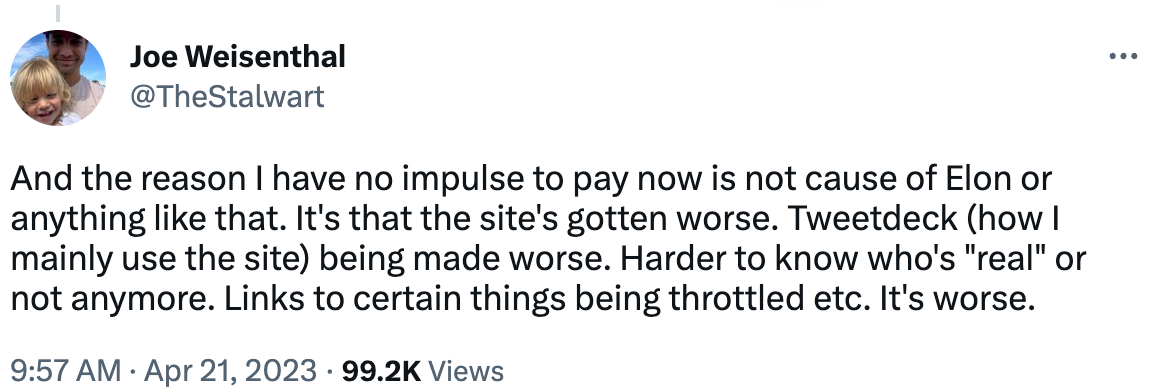

In the media world, we’re watching the unravelling of a major network’s value at the moment. Twitter as a public forum is becoming more and more toxic, causing people to move away from it in dribs and drabs, but dribs and drabs big enough to push it into irreversible decline.

Twitter managed to convince millions of users worldwide that that the juice was worth the squeeze, but of late they’re not too sure, even those who built their careers on Twitter are shunning its attempts at grovelling panhandling. I made my own career on Twitter, at least in part, but the time I spend on the platform now is drastically reduced.

Two major North American news orgs finally said what everyone in media has known for a long time: “It’s not really worth it”, and paused their ‘contributions’ to the network, robbing it of yet more value. NPR’s CEO John Lansing told his team “Twitter no longer has the public service relevance it once had” – it’s become more of a toxic back alley and whatever minimal traffic and conversion it once drove has winnowed further. The connections within the network are fewer, and of lesser value than at any point in its recent history.

When I started thinking about networks, it struck me that I’d started one in my teens - a small but rather successful one – without really thinking about it. I helped pick a dinghy fleet for my country.

In the late 90s I was sailing a Laser 4.7, which is the smallest of the three options for what was then known as the Laser (Now known as the ILCA because of a messy court case). The 4.7 is/was a rather uninspiring, underpowered boat but the only real singlehanded option that was any fun to sail (in my opinion) and had any sizeable fleet to race against. It was a leap from that to the Laser Full Rig in terms of physicality. Per the image below, you top out in the 4.7 at 55kg bodyweight. The reality is that to sail the Full Rig well you need to be 80kg, not 60kg - that’s a 25kg gap. I was too scrawny & weak to handle the bigger rig, and I was not alone in that dilemma. Kids who really wanted to sail something with more ‘ooomph’ would try to sail the full rig despite risking injuring their back in doing so. There was nothing in between it and the 4.7 - except there was.

Ireland hadn’t embraced the middle child in the Laser family yet. The Laser Radial existed in big fleets elsewhere, but there were none in Ireland. And because there were none in Ireland, nobody really wanted to be the first person to get one, because there’d be nobody to sail against. There was no network.

But then we did. A handful of us, including myself and Rory Fitzpatrick (Athens Olympian and coach to Ireland’s silver medallist Annalise Murphy) in Dublin, and a group of lads we knew who sailed out of Monkstown, Cork, after a bit of dancing about, decided we’d collectively be the first ones to take the leap. And so one winter, we all got Radial rigs. And the next summer, we had each other to race against, the boats and the racing were fun, and quickly others wanted in. 27 years later, the Irish Radial fleet still regularly breaks 50 boats at regional events, with kids and adults for whom it’s a better fit than either of the other options turning out in droves. The juice quickly became worth the squeeze, and has remained so ever since. It’s a nice legacy we all left Irish sailing.

If I had to visualize the decision-making that went into this on my part, here’s how it would look. I liked strict one-design boats - where each boat is identical. And I had previously had an experience with a fleet too small to be fun or develop me as a sailor. I didn’t want that again.

So I wanted a big, uniform fleet.

😬 I had been sailing a L’Equipe with a good friend. We were early adopters of this boat, we were the speculative network-builders, we hoped the juice would be worth the squeeze. And while it was a fun and very uniform boat, it never took off. There were limited numbers of them to sail against in Ireland. The motivation of having decent-sized fleets to go visit in France and on continental Europe was never enough to push enough Irish and UK people to buy them at scale. Fun to sail, but disappointing to race, as a result.

🤑 The Mirror dinghy fleet in Ireland was huge but it never really interested me - I had a few bad experiences in the boat early on and it soured me on them. The top sailors spent a lot on their boats to be competitive, and success was something of an arms race. The juice was arguably worth the squeeze, but it was expensive to buy a glass of that juice. They boasted huge fleets, but the difference between the top boats and even the middle of the fleet could be thousands of euros. (There were other factors I saw as negatives too - the boats were wooden, requiring a lot of maintenance, and also fragile as a result, constantly being dented and holed during a summer of fun junior sailing). Great for fleet size. Not great for equality of opportunity.

🧐 The Laser Radial. Lasers came in three rig sizes, but Ireland had only developed sizable fleets in the large (Full rig) and the small (Laser 4.7). There were large Radial fleets all over the world, but not in Ireland. The wonderful thing about Lasers across the board was their absolute uniformity. Strict class rules meant every component on the boat was uniform, it was true one-design racing and there was, effectively, a cap on spending. You couldn’t buy extra performance. They had their design flaws, for sure, but every single boat had the exact same design flaw, without fail. The boats aged reasonably slowly, so you weren’t constantly buying fresh gear to be in with a fair shout of winning. Because the boats were interchangable (everything but the bottom half of the mast and the sail was uniform across all three sizes) there was a baked in second-hand market too. The juice seemed worth the squeeze. But we needed to build a fleet for the middle child from scratch. We still had no network.

In reality, we weren’t building a network from scratch - we were versioning an existing network, two existing, adjoining networks actually, both of which were accelerants to the network we wanted to build. One (the 4.7) was the on-ramp, the other (the Full rig) was the natural off-ramp. We were building the pass-through network.

That off-ramp was a doozy. The Laser Radial was part of a progression path. The end point of that pass-through journey – the Laser Full Rig – had been around since 1970 and had just been selected as an Olympic boat for the 1996 games. Neither the Mirror nor any other boat on the diagram above was part of a network that connected so directly to the Olympics. We had reason to be confident that that endpoint was a significant enough draw that any initial momentum we could kick off would build without too much effort.

We didn’t think of it in those terms, obviously, or that deeply, because we were a bunch of spotty 16-year-olds who just wanted to find a fun boat to race that wouldn’t break our backs, or the bank.

There are may ways to think of this kind of decision-making. If you’re trying to build a network, especially where none exists, you have to think about existing behaviors, needs, and if you can tap into the power of existing networks to kick off your own, so much the better.

At Noan, for example, we’re creating a marketplace of experts, connecting them with a network of our client businesses. We have to build both sides, and we’ll do so by tapping into other networks to do so.

If there was one thing I wish someone had opened my eyes to as a youngster, when I was choosing this dinghy and more broadly in the circles I had around me, it’s the nature and value of the networks I was part of, and that I was creating in school, through friendships and sport. I was oblivious to networks then. I’m somewhat more attuned to them now. Networking is a dirty word to some people, it’s synonymous with transactional relationships, reducing everything to commerce. In reality, your network(s) represent a dynamic web of shared reliances, supports and interests. They are the ever-morphing fabric of humanity. They should be nurtured, tended to, pruned, fertilized - all those metaphors. How you choose and foster your own networks of friends, colleagues, competitors or employees likely, subconsciously, comes down to a matrix like the one above.

Plot two of the defining values of any network you’re a part of on the horizontal and vertical axes – honesty & humor, love of crochet and twitter, number of scarves owned & boat ownership, beard length and fondness IPA – whatever your fancy – and you’ll find that your strongest connections group toward the top right. They are the people from whom and for whom the juice is worth the squeeze.

😢 Totally unrelated: My dad’s aunt Peggy was a trailblazing feminist, an educator and an inspiration. She worked as a Loreto nun in Kenya for more than 40 years, teaching girls, including Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Maathai. She passed away this week, aged 92. I loved her dearly, and made this radio project about her life when I was in college. Her story is great, I’m delighted I captured it in her own words and voice, and I hope you like it.